I’ve undertaken a project: reading all of the late, great Joanna Russ’s books in chronological order and sharing my thoughts on them in a series of posts. There’ll be some additional reference material where appropriate from books like Mendlesohn’s On Joanna Russ anthology and possibly Jean Cortiel’s Demand My Writing, too, but mostly just discussions of the books themselves.

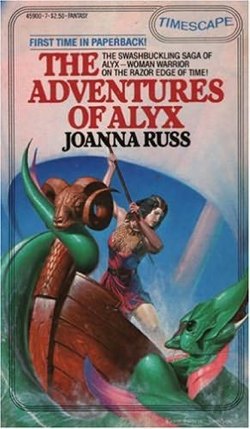

To start, there’s The Adventures of Alyx. Technically, this isn’t the “first” book chronologically as it was actually published in 1986, but the stories themselves come from 1967-1970. Also, it does contain her first (short) novel, Picnic on Paradise, which was part of the Alyx story-cycle—so, it’s the first on the reading-list. The Alyx stories collected together create a sort of tapestry-novel, and that’s how I’ll be discussing them—as a complete book, The Adventures of Alyx. (I do wonder why it took sixteen years to publish the stories that so obviously made a complete tale in one book, but I suppose I’ll never know.)

What begins as Leiber-esque fantasy in the story “Bluestocking” (originally published as “The Adventuress”) traverses time and space into science fiction and finally metafictional commentary, creating a wonderful mosaic of stories that both entertain the reader in the conventional way—adventures, deadly danger, mysteries to solve—and also provoke thought about the roles of women in speculative fiction. It’s also open to quite a bit of reader interpretation, by the end.

For example, the first essay in Farah Mendlesohn’s On Joanna Russ collection is a piece by Gary K. Wolfe about these stories, “Alyx among the Genres.” I read the essay before actually reading the book, which gave me a strange angle on the stories—as if I’d been there before, but I hadn’t. The essay, in a way, set me up to read the Alyx stories as doubly fictional: stories produced by the young woman character of the final story, “The Second Inquisition,” who potentially represents a young Russ herself. It’s a brilliant essay that digs deep into the multilayered possibilities of the Alyx stories; I recommend giving it a read, too, if you have a taste for insightful criticism that picks at bits of the tale you never quite noticed.

Having seen the book in that light—the stories as stories written by a fictional character in her fictional imaginary universe, so that there are two layers of “fiction” in the text—I can’t unsee it; it seems perfect. (It’s not an insight original to me, though, so it’s only fair to credit Mr. Wolfe. Who can say if I would have put the pieces together, otherwise?)

Aside from that lovely, tricksy construction, there’s quite a bit to say about the Alyx stories. For one, they’re predominantly heterosexual, which came as a bit of a shock to me, having started my reading of Russ with quintessentially lesbian/queer texts (The Female Man, for example). I like it, though; straight women need to see themselves presented as capable and strong in fiction as much as queer women, and often see it even less, as if the addition of a male love interest saps the strength of a heterosexual female character. The frank discussions of sexuality, sensuality and women’s desire in The Adventures of Alyx revolve around Alyx herself, generally, and how she has dealt with and loved men—an abusive husband in one tale who drove her away to a pirate captain, who she eventually leaves, a lover in the SFnal story who is used against her by the antagonist, another lover when she is the potentially imaginary construction of the young woman in “The Second Inquisition,” and of course her intimate, emotional relationship with Machine in Picnic on Paradise.

There are men in Alyx’s life, but they are never her superiors—even with her abusive husband, it is made clear that she is the stronger of the two when she defeats him. In the best relationships, she is equal to them, and in the less developed, she’s the dominant figure. Alyx is the opposite of the women who would normally populate a swashbuckling adventure or SFnal survival story—she’s the hero, not the damsel in distress or the love interest. That is where I find the value of these stories/this book, as well as the reason I enjoyed them so much. It’s just awesome to read about a strong woman doing interesting, dangerous things, in control of her own life.

As previously mentioned, the first couple of Alyx stories are Leiber-esque fantasy (one story contains a reference to Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser, so it’s hardly by accident). The difference is that in place of the male hero, we have Alyx, tougher than hell and ready to fight when she needs to, but also capable of softness toward her estranged daughter as she remembers her and to the young woman in “Bluestocking” who she’s trying to help escape a bad arranged marriage. The development of Edarra, the young woman, provides a perfect parallel to the deadly intensity of Alyx—she starts out spoiled and whiny, but over the course of their trip, discovers sword-fighting and her own central desires. She becomes a real person, not simply a piece on a board to be moved about, and does so by developing a sense of independence. It’s a pleasure to watch unfold.

Really, I love the women of Alyx’s stories, most especially Alyx herself. What a refreshing surprise it is to see a woman hero of an adventure story, and later on in the more SFnal tales like “The Barbarian” to see that she’s not just a tough fighter but also remarkably intelligent as she works her way through the tricks of the man from the future who’s pretending to be a wizard. She’s competent, capable and genuinely well-developed as a person. Even today, there aren’t many women playing the protagonists’ role in stories like these.

Though, the shape and focus of the stories does change with the truly science-fiction tale, Picnic on Paradise, Russ’s first short novel. In this, Alyx is a time-traveler sent off to rescue a group of rich tourists trapped on a pleasure-planet which is the subject of a war. It’s a long, gruesome, upsetting story that yanks hard at the readers’ emotions—it’s no longer a playful adventure, but a survival tale where the best and brightest don’t make it, and the hero herself nears the breaking point. It puts Alyx through the wringer and allows the reader to see a depth of character hidden in the prior stories by their more superficial nature. It’s an engrossing read, and the survival-story is something Russ will come back to later in We Who Are About to Nonetheless, it’s tonally very different from the other three stories, though Alyx remains recognizable.

The final story, “The Second Inquisition,” is where it gets weird. This is a contemporarily set story, about writing, reading, and the world of books for a young woman who is otherwise trapped, completely trapped, by her parents’ dysfunctional marriage, her suburban life and the expectations that dictate what she may do with her future. It’s the most directly feminist tale of the bunch, also; the others are feminist in that they present women as strong, equal humans capable of being the lead, but they are not as directly didactic as “The Second Inquisition” becomes. The discussions of race, gender and sexuality in this final tale are all intensely written through clipped, realistic dialogue, shown to the reader through the eyes of the young woman. In the end, the bit about daughters and granddaughters and whatnot seems to imply that the young woman is the creator of Alyx and the shaper of her, potentially her writer.

It’s a mind-bending ending that provokes quite a lot of thought and changes the way a reader looks at the other stories in The Adventures of Alyx, as not just tales written by Russ but stories written by a character who might be a young Russ or who might be another fictional creation—stories written by her as a means of escape.

I deeply enjoyed reading these stories, separately and as a whole; they provide both flat-out entertainment—they really are fun and exciting—and thoughtful commentary that’s likely to stick with the reader, as it did me, for some while after finishing the book. The writing is, of course, phenomenal; I probably don’t even need to bother to say that.

The next book, however—And Chaos Died—provoked a totally different response from me, as I’ll explain next time.

Lee Mandelo is a multi-fandom geek with a special love for comics and queer literature. She can be found on Twitter and Livejournal.